Nature’s Reflections – Whooping Crane

This large bird still on the endangered species list

The whooping crane (Grus americana), is named for its unique trumpet-like call that can be heard for several miles. It is North America’s largest bird, standing 45 to 50 inches tall with a wingspan of 90 inches. Mature birds are pure white with black wing tips, dark legs, a long neck, a long, dark, pointed bill and a bumpy red crown. The bumpy red patch on the head, a trait shared with the close relative sandhill crane, serves to indicate the bird’s mood – becoming bright and expanded when agitated or excited. Whooping cranes and sandhill cranes are the only two cranes found in North America.

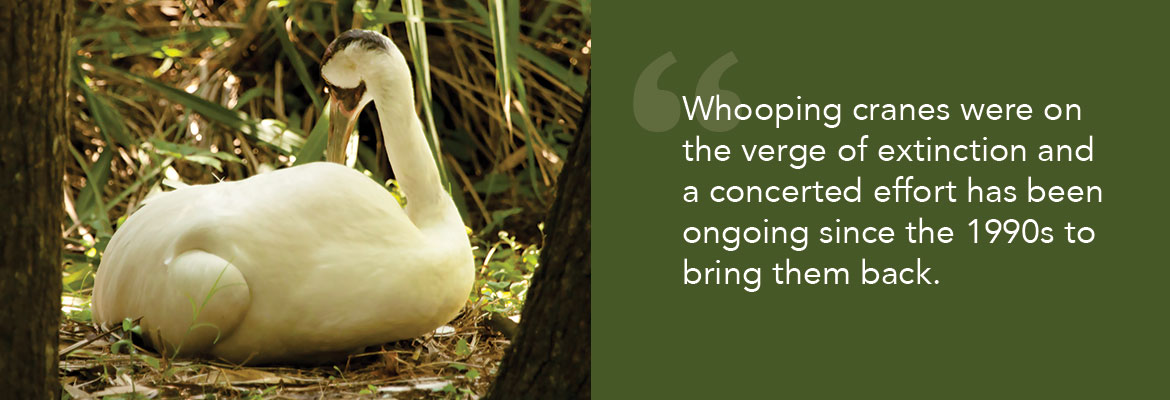

Whooping cranes are one of the most beautiful birds and one of the rarest. This endangered species once wintered in Florida, but habitat loss virtually wiped out most of its population. The birds were on the verge of extinction and a concerted effort has been ongoing since the 1990s to bring them back. Florida’s small whooping crane population is now mostly non-migratory.

A project to restore the migratory whooping crane began in 2001. Each winter, captive-raised and released whooping cranes are led by ultra-light aircraft from Wisconsin to Florida. The idea of the project is that once these birds are taught the north-to-south migration route, the birds will continue to make the journey on their own.

Whooping cranes mate for life, but will take a new mate if one dies. Whoopers live 22 to 24 years in the wild. Sexes are similar in appearance, although males are larger – weighing about 16 pounds. Nests are usually built over standing water and pairs return to nest in the same area each year. Females lay two blotchy, olive-colored eggs in late April to May. Incubation takes 30 days. Within twenty-four hours of hatching, the pale brown chicks leave the nest to follow the parents. Both parents care for the young. The young stay with the parents for a year, learning to forage for seeds and roots, insects, snakes, frogs and small rodents. They can fly at three months, and have their full adult plumage by the end of the second summer. At five years they are ready to choose a mate and begin a family.

To learn more about the ongoing migratory project, visit www.bringbackthecranes.org.

Column & photos by Sandi Staton – sandi.staton@gmail.com

Read the full Nature’s Reflections article in the December 2017 SECO News.